Scoping is one of the first and main thing that we do the moment we get engaged, after the customary celebratory drinks. In all projects, scope is always key, moreso in auditing and consulting, in standards compliance, be it PCI, ISMS, NIST 800s, CSA or all the other compliances we end up doing. Without scope there is nothing. Or there is everything, if you are looking at it from the customer’s viewpoint. If boundaries are not set, then everything is in open season. Everything needs to be tested, prodded, penetrated, reviewed. While this is all good and all, projects are all bounded by cost, time and quality. Scope determines this.

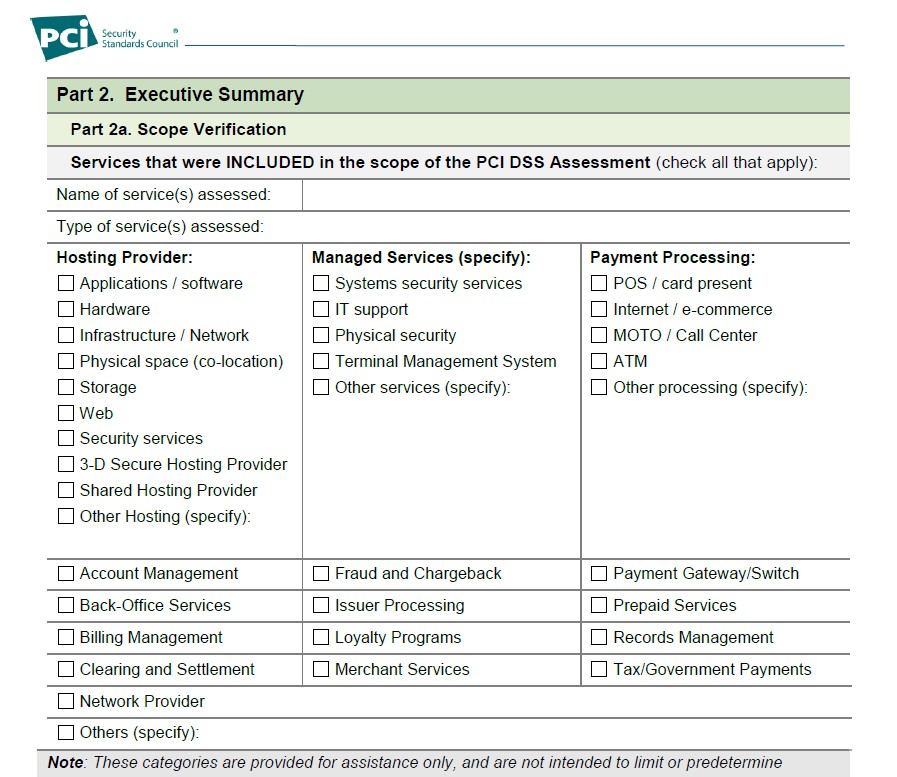

In PCI, scoping became such a tremendously huge issue that the council deem it necessary to publish an entire supplemetary document called “Guidance for PCI DSS Scoping and Network Segmentation” back in December 2016. Now, here is a trivia for you, from someone who has been doing PCI for donkey years. Did you know that this isn’t even the first attempt at sorting out scope for PCI-DSS?

Back in 2012, there was a group Open Scoping Framework Group that published the extremely useful Open PCI-DSS Scoping Toolkit that we used for many years as guidance before the council amalgamated the information there into formal documentation. This was our go-to bible and a shout out to those brilliant folks at http://www.itrevolution.com for providing it, many of its original concepts retained when PCI council released their formal documentation on scope and eventually within the standards itself. YES, scoping is finally in the iteration of v4 and v4.0.1 for PCI-DSS in the first few pages, so that people will not get angry anymore.

Or will they?

We’re seeing a phenomenon more and more in the industry of what we term as scope creep. Ok fine, that’s not our word. It’s been in existence since the fall of Adam. Anyway, in PCI context, for no apparent reason some of our customers come back to us and state their consultants, or even QSAs insists on scope being included — for NO REASON except that it is MANDATORY for PCI-DSS. Now, I don’t want to say we have no skin in the game, but this is where I often end up arguing with even the QSAs we partner with. I tell them, “Look, our first job here is to help our customers. We minimize or optimize scope for them, reducing it to the most consumable portion possible, and if they want to do anything extra, let them decide on it. We’re not here to upsell Penetration testing. Or segmentation testing. Or Risk Assessment. Or ASV. Or Policies and Procedures. Or SIEM. Or SOC. Or Logging. Or a basket of guavas and durians.” Dang it, we are here to do one thing: get you PCI compliant and move on with our lives.

The trend we see now is that everything seems to be piled up to our clients to do this and to do that. In the words of one extremely frustrated customer: “Everytime we talk to this *** (name redacted), it seems they are trying to sell us something and getting something out of us, like we are some kind of golden goose.”

Now, obviously, if you are a QSA company and doing that:- STOP IT. Stop it. It’s not only naughty and bring disrepute to your other brethren in the industry, it’s frowned upon and considered against your QSA code! Look at the article here.

Now PCI scoping itself deserves a whole new series of articles but I just want to zoom down to a particular scoping scenario that we recently encountered. It’s in a merchant environment.

Now many of our merchants have either or both of these scopes: Card terminal to process card present at the stores and E-Commerce site. There is one particular customer with card terminal POI (point of interaction), or traditionally known as EDCs (Electronic Data capture). Basically this is where the customer comes, take out the physical card and dip/wave it to this device at the location of the stores. So yes, PCI is required for the merchant for the very fact that the stores have these devices that interact with cards. Now what happens after this?

Most EDCs have SIM based connectivity now, and it goes straight to the acquirer using ISO8583 messages. These are already encrypted on the terminal itself and routes through the telco network to the bank/acquirer for further processing. Other ways are through the store network, routing back to the headquarters and then out to the acquirer. There are reasons why this happens, of course, one would be the aggregation of stores to HQ allows more visibility on the transactions and analysis of traffic. The thing here is, the terminal messages are encrypted by the terminals, that the merchants do not have any access to the keys for decryption. This is important.

Now, what happened was that some QSAs have taken into their mind that because the traffic is routed through the HQ environment, the HQ gets pulled into scope. And therefore , this particular traffic must be properly segmented and then segmentation PT needs to be performed. This could potentially lead to a lot of issues, especially if your HQ environment is populated with a lot of different segments – it could constitute multiple, tiring, tedious testing by the merchant team….or it could constitute a profitable service done by your ‘service providers’ (Again, if these service providers happen to be your QSA, you can see where the question of upsell and independence come from).

Now here’s the crux. We hear these merchants telling us, oh, their consultant or QSA say that it’s mandatory for segmentation PT to occur in this HQ environment. The reasoning is that there is card data flowing through it. Regardless whether it is encrypted or not, as long as there is card data, IT IS IN SCOPE. Segmentation PT MUST BE DONE.

But. Is it though?

The whole point of segmentation PT is that it demarcates out of scope to in-scope. By insisting to have segmentation PT done, is to concede that there is an IN-SCOPE segment or environment in the HQ. The smug QSA nods, as he sagely says, “Well, as QSAs, we are the judge, jury and executioner. I say there is an in scope, regardless of encryption.”

So, we look at the PCI SSC and the standards, and let’s see. QSAs will point to page 14 of PCI-DSS v4.0 standards under “Encrypted Cardholder Data and Impact on PCI DSS Scope”.

Encryption alone is generally insufficient to render the cardholder data out of scope for PCI DSS and does not remove the need for PCI DSS in that environment.

PCI-DSS v4.0.1 by a SMILING QSA RUBBING PALMS TOGETHER

Let’s read further this wonderful excerpt:

The entity’s environment is still in scope for PCI DSS due to the presence of cardholder data. For example, for a merchant card-present environment, there is physical access to the payment cards to complete a transaction and

there may also be paper reports or receipts with cardholder data. Similarly, in merchant card-not-present environments, such as mailorder/telephone-order and e-commerce, payment card details are provided via channels that need to be evaluated and protected according to PCI DSS.

So far, correct. We agree to this. Exactly like what was mentioned, PCI is in scope. The question here is, will the HQ gets pulled in scope just for transmitting encrypted card data from the POIs?

Let’s look at what causes an environment with card encryption to be in scope (reading further down the paragraph)

a) Systems performing encryption and/or decryption of cardholder data, and systems performing key management functions,

b) Encrypted cardholder data that is not isolated from the encryption and decryption and key management processes,

c) Encrypted cardholder data that is present on a system or media that also contains the decryption key,

d) Encrypted cardholder data that is present in the same environment as the decryption key,

e) Encrypted cardholder data that is accessible to an entity that also has access to the decryption key.

So let’s look at the HQ scope. Does it cover the following 5 criteria for in-scope PCI-DSS dealing with encrypted card data? There is no decryption or encryption process done. The encrypted cardholder data is isolated from the key management processes. The merchant has no access or anything to do with the decryption key.

So now you see the drift. Moving down the paragraph, we find noted that when an entity receives and/or stores only data encrypted by another entity, and where they do not have the ability to decrypt the data, they may be able to consider the encrypted data out of scope if certain conditions are met. This is because responsibility for the data generally remains with the entity, or entities, with the ability to decrypt the data or impact the security of the

encrypted data.

In other words: Encrypted cardholder data (CHD) is out of scope if the entity being assessed for PCI cannot decrypt the encrypted card data.

So now back to the question, if this is so, then why does the merchant still need PCI? Well, because it’s already provisioned above: For example, for a merchant card-present environment, there is physical access to the payment cards to complete a transaction and there may also be paper reports or receipts with cardholder data.

So therefore, stores are always in scope. The question we have here is, if the HQ or any other areas are pulled in scope simply for transmitting encrypted CHD as a passthrough to the acquirer. In many way, this is similar to why PCI considered telco lines as out of scope. They simply provide the highway where all these encrypted messages travel on.

Now, of course, the QSA is right about one thing. They do have the final say, because they can still insist on customers doing the segment PT even if its not needed by the standard. They can impose their own risk-based requirements. They can insist the clients do a full application pentest or ASV over all IPs not related to PCI. They can insist on clients getting a pink elephant to dance in a tutu in order to pass PCI. It’s up to them. But guess what?

It’s also up to the customer to change or have another opinion on this. There are plenty of QSAs about. And once more, not all QSAs are created equal as explored in our article here. Here we debunk common myths like whether having a local QSA makes any difference or not (it doesn’t), and whether all QSAs interpret PCI the same way (they don’t) and how important independence and conflict of interest should play a role, especially in scoping and working for the best interest of the customer, and not peddling services.

So, if you want to have a go with us, or at least just get an opinion on your PCI scope, drop a message to pcidss@pkfmalaysia.com and we will get back to you and sort out your scoping questions!